A botanical approach to discovering plants in the Lofoten Islands

- Text, diagram Stéphane Martineau - (photos: hiking-lofoten and Stéphane Martineau)

Most people are struck by the rugged wild mountains rising out of the sea when they first reach the the Lofoten Islands that stretch 160 km in a small mountain range from the Island of Hinnoya in the north east to the Skomvaer Lighthouse in the south west.

The mountains of the Lofoten Islands contain the oldest rocks found in northern Europe and contain monzonite, mangerite and gneiss which are extremely erosion-resistant and have been there for over 3 billion years. The most significant changes to the landscapes occurred during the Quaternary period, i.e. from around 2.5 million years ago to the present day. The ice ages are mainly responsible for the current appearance of the landscape that resulted in rugged mountains, isolated peaks, trough-shaped glacier valleys that open into the sea (fjords) and straits that separate the present islands, beaches created from the combined effect of freezing, marine erosion, the abrasive effect of the glaciers and deposits that remained after the glaciers melted.

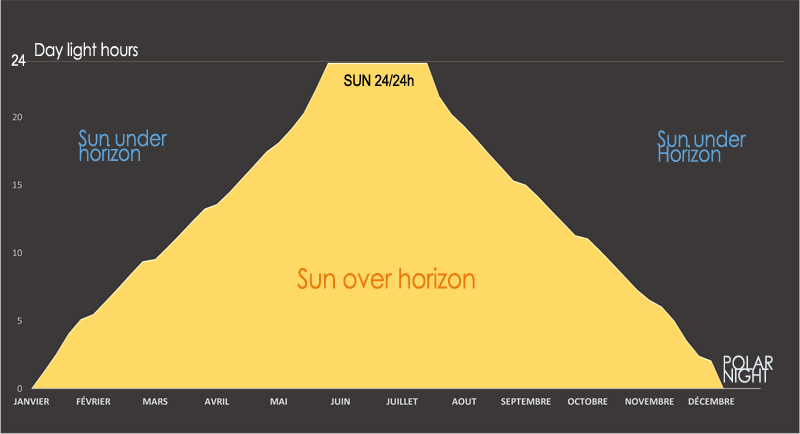

The Lofoten Islands, which are located to the north of the Arctic Circle, are subject to a harsh climate tempered by relative mildness provided by the Gulf-Stream, as well as unusual conditions of light. In midsummer the sun still shines at midnight and remains above the horizon from 28 May to 14 July. In the winter, on the other hand, the islands are plunged into darkness from 7 December to 5 January.

Rocks, climate and plants…

Jagged mountain ranges that peak at around 1100 m, glacial moraines and lakes, bottoms of valleys covered with peat, alluvial terraces and beaches, rocky coastlines battered by the waves, the nature of the rocks and ground, extremely variable light and quickly changing climatic factors including snow for part of the year, not forgetting the presence of people and their activities, particularly livestock breeding, create a combination of conditions that influence and determine the plants that grow in the Lofoten Islands.

Topography and climate determine the wide variety of natural habitats, and particularly the vegetation. Human activities have relative, sometimes significant, influence on certain environments by modifying their diversity by encouraging certain species over others (grazing land), destroying (deforestation) or adding species that would not have grown naturally in these places, or at least not as quickly. But all indigenous plants are well suited to the environments in which they grow..

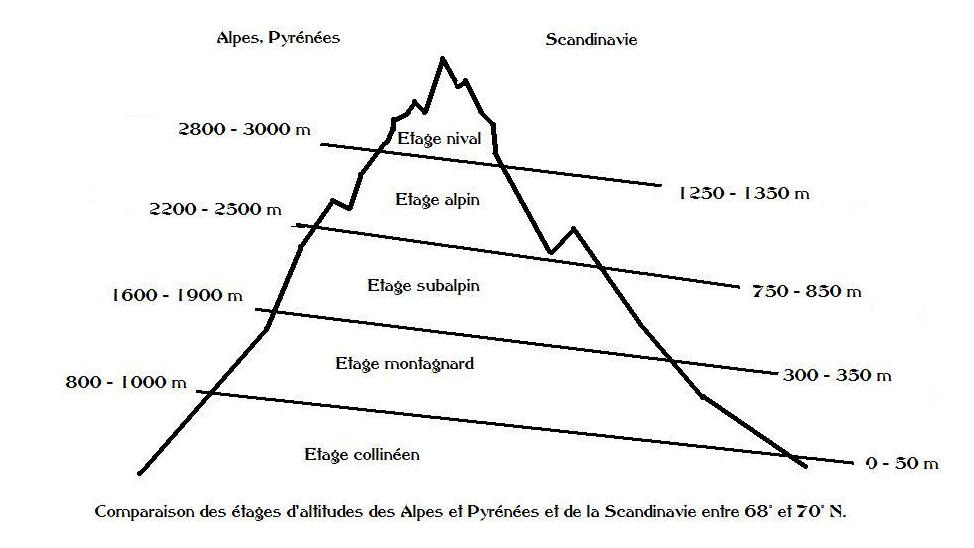

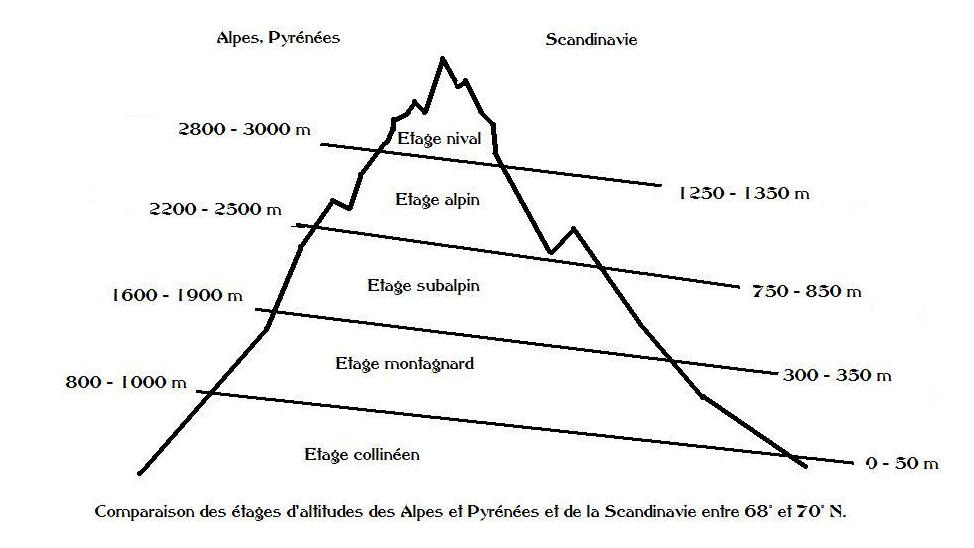

In the Lofoten Islands plants are found that typically grow in high alpine altitudes, particularly on the north- or south-facing rocky slopes and grass. The hard erosion-resistant rocks that do not create deep, rich soil are only suitable for plants that require few nutrients. This is also where the harshest climatic conditions are found that demand the greatest degree of adaptation from plants if they are to survive and reproduce. However, due to the very northerly position of the Lofoten Islands compared to southern Norway and, naturally, to the French Alps and Pyrenees with their very characteristic tiering of vegetation, certain alpine plants grow even on the coast, on the rocky slopes and sandy and marine deposits of the beaches and alluvial terraces, thus mixing unexpectedly with plants whose requirements are totally different.

In the Lofoten Islands plants are found that typically grow in high alpine altitudes, particularly on the north- or south-facing rocky slopes and grass. The hard erosion-resistant rocks that do not create deep, rich soil are only suitable for plants that require few nutrients. This is also where the harshest climatic conditions are found that demand the greatest degree of adaptation from plants if they are to survive and reproduce. However, due to the very northerly position of the Lofoten Islands compared to southern Norway and, naturally, to the French Alps and Pyrenees with their very characteristic tiering of vegetation, certain alpine plants grow even on the coast, on the rocky slopes and sandy and marine deposits of the beaches and alluvial terraces, thus mixing unexpectedly with plants whose requirements are totally different.

Different environments encountered when hiking…

Beaches and marshlands...

Towards the beaches and marshlands the plants have to cope with the sea, sometimes an inlet of water without too many waves such as in the marshes and saline scrubs, or much rougher seas particularly during bad storms on the exposed beaches. They are constantly in and out of seawater. The soil is very salty for the roots. Rapid changes occur in the water levels and therefore in temperature and salinity. For plants that are the furthest away from the sea, in the dunes for example, the parts above ground are subjected to sea mist while the underground parts are soaked in either fresh or salt water. The winds sometimes blow hard and may either uproot the plants or cover them with sand. There are many plants that excrete salt, that have long roots and sometimes a thick cuticle to limit evaporation and salt burn..

Rocky coasts...

The situation is similar on the coastal rocks where seashore rock plants are often covered with seawater. Those that grow higher up that are protected from the seawater are, nevertheless, subject to the wind and salty sea mist. They are often crassulaceous (succulents) with a thick cuticle that grow as low bushes.

Alluvial terraces...

On the alluvial terraces, which is an environment with rich, fertile deep soil, there are many classic seashore, plain, sub-montane and mountain varieties. The wide range of environments and plants, both on the seashore and in the mountains, is one of the most unusual features of Norway and particularly the Lofoten Islands. This is also virtually the only land that people farm and therefore the only place you will find the plants, often annuals, associated with farming.

Wood and forests...

Even though there are few forests in the Lofoten Islands, some deciduous forests still remain here and there, particularly classic birches in the boreal zone. These shady forests with their deep, humid soil are home to other varieties of plants. Conifers such as spruce trees have been replanted and under this virtually permanent shade the soil is poorer and more acidic.

Ponds, lakes and rivers...

In the ponds, lakes and rivers various aquatic plants can be found as soon as you step into the water either with or without a current. The shoreline very often includes damp moss and plants that grow on the banks very close to the water or within the immediate vicinity.

Peatland...

Peatland, which is rich in sphagnum moss that holds water like a sponge, is acidic and poor in nutrients. It is home to plants that are very well adapted to this specific environment, particularly insect-eating plants such as the sundew (drosera), that uses animal protein to compensate for the poorness of the soil.

Heathland...

The heathland is considered alpine, dominated by the shrubs and sub-shrubs of environments with acidic soil that are characteristic of heather and blueberry shrubs, together with lichen, moss and grasses. In the French Alps or Pyrenees these environments are found at altitudes of over 1500 m but, like the grasslands, mountain rocks and valleys, they descend much lower in this boreal zone and sometimes reach the shoreline, which means you can pick blueberries on the beach.

Alpine grasslands...

The alpine grasslands, which are rich in species that are often small and brightly coloured, are generally dominated by grasses. The plants that make up the grassland and its floral diversity depend on which way the mountain slope is facing, whether it is exposed to the sun.

In terms of the grasslands, the snow may remain for a long time and shorten or postpone the flowering time, particularly in the valleys where the snow can stay all summer on certain slopes and in the hollows.

Whether moraines, scree and cliffs...

Whether moraines, scree or cliffs, in the Lofoten Islands you encounter at all altitudes mountain rocks, bare bedrocks or moraine deposits, erratic rocks or rocks of glacial cirques. In the French Alps or Pyrenees they are characteristic of altitude, or high altitude, together with the range of plants that develop there. In comparison, at these latitudes alpine rock plants grow from the sea shore to the peaks, as far up as the permanent snow that can be found here at 1300 m.

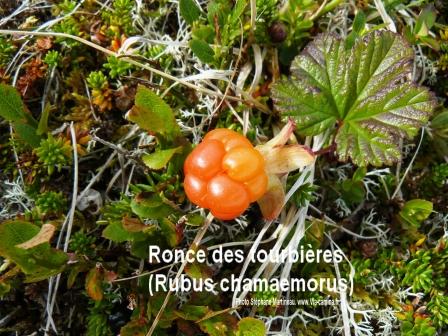

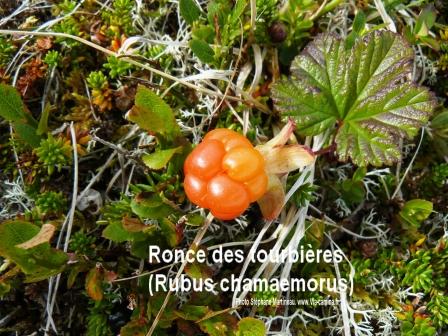

Summer fruits

When you hike in the Lofoten Islands you can pick a variety of wild berries such as blueberries, cranberries, blackberries, crowberries and redcurrants, but the star of the show is found in the humid heathlands, a delicious fruit that melts in the mouth called the cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus). It grows in abundance around the Arctic Circle in the boreal forest area and tundra. The cloudberry is called “chicouté” and “plaquebière” (from “plat de bièvre “ in other words “beaver food”) in Quebec. But in Norway the cloudberry is called “multebaer” or simply “multe”.

When you hike in the Lofoten Islands you can pick a variety of wild berries such as blueberries, cranberries, blackberries, crowberries and redcurrants, but the star of the show is found in the humid heathlands, a delicious fruit that melts in the mouth called the cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus). It grows in abundance around the Arctic Circle in the boreal forest area and tundra. The cloudberry is called “chicouté” and “plaquebière” (from “plat de bièvre “ in other words “beaver food”) in Quebec. But in Norway the cloudberry is called “multebaer” or simply “multe”.

It is a small hardy perennial that grows quite close to the ground, creeping and slightly velvety, whose stalks do not have thorns. The leaves are simple and rough, kidney shaped, lobed and toothed. From mid-June you may come across the plant in flower, a single white flower measuring approximately 20-30 mm, but you will only find fruit on female plants because this species has different male and female flowers. The edible fruit, which turns orange when it ripens in summer, comprises a cluster of small fleshy spheres (drupelets) similar to blackberries and raspberries. The acidic yet sweet flavour, which is slightly sour, is comparable to that of the lychee.

This delicious berry is found in marshlands, heathlands and damp forests, tundra, on acidic peaty soil and, in the Lofoten Islands, virtually at sea level up to around 650 m. Cloudberries are rich in vitamin C and the juice, which is easily preserved, was a remedy against scurvy at sea. Roald Amundsen and his men ate jam made of cloudberries when they conquered the South Pole. It has always been an important wild fruit for families in northern Norway, to the extent that regulations stipulate that it may only be picked by the owners of land where the fruit grows. Cloudberries play a vital part in the economy and a range of varieties are now cultivated. It is still possible to pick them here and there, however, or buy them in small punnets at local markets. They can be eaten as they are, as juice, in tarts, jam, jelly and liqueur.

This delicious berry is found in marshlands, heathlands and damp forests, tundra, on acidic peaty soil and, in the Lofoten Islands, virtually at sea level up to around 650 m. Cloudberries are rich in vitamin C and the juice, which is easily preserved, was a remedy against scurvy at sea. Roald Amundsen and his men ate jam made of cloudberries when they conquered the South Pole. It has always been an important wild fruit for families in northern Norway, to the extent that regulations stipulate that it may only be picked by the owners of land where the fruit grows. Cloudberries play a vital part in the economy and a range of varieties are now cultivated. It is still possible to pick them here and there, however, or buy them in small punnets at local markets. They can be eaten as they are, as juice, in tarts, jam, jelly and liqueur.

|

Text, diagram and photos Stéphane Martineau, www.via-camina.fr

Stéphane Martineau is a mountain guide and biologist by training, but he is above all, a self-taught man and a nature lover. He carries on with his passions in the Pyrenees, where he leads hiking trips and thematic discovery-walks on the natural environment, flora and fauna. He has contributed in various hiking, "nature" and Pyrenean fauna books. He is also the author of several publications on wild edible plants.

|

This delicious berry is found in marshlands, heathlands and damp forests, tundra, on acidic peaty soil and, in the Lofoten Islands, virtually at sea level up to around 650 m. Cloudberries are rich in vitamin C and the juice, which is easily preserved, was a remedy against scurvy at sea. Roald Amundsen and his men ate jam made of cloudberries when they conquered the South Pole. It has always been an important wild fruit for families in northern Norway, to the extent that regulations stipulate that it may only be picked by the owners of land where the fruit grows. Cloudberries play a vital part in the economy and a range of varieties are now cultivated. It is still possible to pick them here and there, however, or buy them in small punnets at local markets. They can be eaten as they are, as juice, in tarts, jam, jelly and liqueur.

This delicious berry is found in marshlands, heathlands and damp forests, tundra, on acidic peaty soil and, in the Lofoten Islands, virtually at sea level up to around 650 m. Cloudberries are rich in vitamin C and the juice, which is easily preserved, was a remedy against scurvy at sea. Roald Amundsen and his men ate jam made of cloudberries when they conquered the South Pole. It has always been an important wild fruit for families in northern Norway, to the extent that regulations stipulate that it may only be picked by the owners of land where the fruit grows. Cloudberries play a vital part in the economy and a range of varieties are now cultivated. It is still possible to pick them here and there, however, or buy them in small punnets at local markets. They can be eaten as they are, as juice, in tarts, jam, jelly and liqueur.

Even though you may love being alone and be in good physical shape, and there is no risk of being kidnapped and held for ransom here, the nature of the terrain, unpredictable weather and limited number of hikers may have dramatic consequences in the event of an accident, however minor (twisted ankle, a fall, etc.). Mobile phones can’t always find a signal and the nights can be cold and damp even in July…

Even though you may love being alone and be in good physical shape, and there is no risk of being kidnapped and held for ransom here, the nature of the terrain, unpredictable weather and limited number of hikers may have dramatic consequences in the event of an accident, however minor (twisted ankle, a fall, etc.). Mobile phones can’t always find a signal and the nights can be cold and damp even in July…